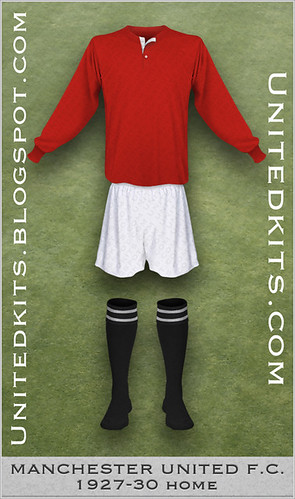

The 1927-28 season saw United revert to their traditional home colours of red and white. New jerseys with white trim inside button collars would be part of the home kit for the next three seasons (the change kit is currently unknown, but it may have been the previous home kit was used in case of a clash):

For the superstitious supporters, it was not merely a coincidence that United won their first two league games upon the return of the red jerseys - beating Bamlett's previous side Middlesbrough 3-0 at home and Wednesday 2-0 away. Sadly, after another injury put Frank Barson out of action, the run of form did not last and United went on a run of 5 games without a win, including a record 7-1 home defeat to Newcastle.

The worst was soon to come however, when in October the club's chairman and benefactor, John Henry Davies, died at the age of 63. His influence and financial backing would be sorely missed in the coming years.

The rest of the season saw United yo-yo up and down the league table. They put five goals past Villa, Derby and Leicester in the league and seven past Brentford in the cup (although they were ultimately knocked out by eventual winners Blackburn Rovers in the sixth round), but they conceded five to Everton before Derby got their revenge with a 5-0 win of their own. By the end of March, United were second from bottom, supporters were grumbling about the way the club was being run and attendances were shrinking.

On April 21st, it looked as if the return to the second division was inevitable as the Reds slumped to a 2-1 home defeat to relegation rivals Sheffield United. There were just three games to go and United needed to win all of them to stay up. Miraculously they did just that by edging out Sunderland and Arsenal with scores of 2-1 and 1-0 respectively, before hammering Liverpool 6-1 at Old Trafford on the final day to finish in a safe 18th place.

Sadly, Barson had played his last game for the club when attempting to make a comeback from injury, he suffered yet another one at Portsmouth. He was given a free transfer to Watford in the summer.

The following season saw United struggle once more. A string of injuries to key players again proved to be their undoing, leading to more criticism of the directors from the supporters who believed they should have been investing more money into the club and securing more quality signings instead of spending small amounts on endless cheap one-game-wonders. This would only intensify in the next couple of years. Following a sequence of sixteen league games without a win, the club's response was to bring in another couple of low budget players. Luckily, one of these was to prove an unlikely hit.

Tommy Reid had been signed from Liverpool, where he usually featured in the reserves. Upon being thrown into the thick of first-team action at United, however, the Scot striker managed an impressive 14 goals in 17 appearances - alongside strike partner James Hanson (who chipped in with 20 goals himself in 1928/29), he made a big contribution to United's turnaround that season. Come May, United had secured 12th place. In time-honoured style, they were knocked out of the cup in their second tie, however.

1929/30 proved to be another unspectacular struggle against threat of relegation. Eight losses in the first eleven games set the tone and in November, United received a 7-2 thrashing by Sheffield Wednesday at Hillsbrough. Once again, the cup run ended at the earliest opportunity after a 2-0 home loss to Swindon Town. The season's few high points were the 5-0 victory over Newcastle in late December and the club's first ever win at Maine Road (Reid scoring the only goal). Off the pitch, United were becoming increasingly troubled financially, as the poor football being played at Old Trafford and the growing level of unemployment combined to reduce attendances further. United needed an average gate of around 30,000 to break even, but that had not been the case for much of the decade and the debts were now racking up.

Things took a further downward turn during 1930/31. United conceded 26 goals in the first five games of the season, when they were beaten by Villa and Middlesbrough before being demolished 6-2 at Chelsea and 6-0 at home by Huddersfield Town. Newcastle then came to Old Trafford and put seven past the Reds. The disquiet amongst the support grew, the crowds shrunk and before long the Supporters Club, led by a Mr. George Greenhough, proposed a boycott if the board failed to meet with them to discuss the state of the club. Their demands were that the club find a new manager and buy some new players, invest in a new scouting system, and elect members of the supporters club to the board.

It was suggested that the match against Arsenal on 18th August should not be attended by fans and a meeting was held the day before at Hulme Town Hall with 3,000 supporters listening to Greenhough and former club captain Charlie Roberts make their cases for and against the boycott.

Greenhough insisted that as the board had so far failed to act on the Supporters Club's demands (or even to meet with them to discuss matters), the game should be boycotted. Roberts argued that the proposed action would affect the players, who were not to blame for the club's situation, rather then the board, who were. The supporters, however voted overwhelmingly in favour of Greenhough's plan.

By 3 O'Clock the following afternoon, however, it became clear that those 3,000 in attendance for the meeting were in the minority, as the match drew the highest gate of the season so far, when 23,406 turned up despite the adverse weather. Inevitably, United lost, as they did the following game, marking a sequence of 12 successive defeats.

By the end of the season, Bamlett had been let go (with four matches still to be played, Club Secretary Walter Crickmer taking over as temporary manager - presumably in an effort to save money) and United were at the foot of the table, having managed to win just seven games. They had conceded 115 goals, scored only 53 and equalled Middlesbrough's record for lowest number of points scored in a first division season with just 22.

The worst was soon to come however, when in October the club's chairman and benefactor, John Henry Davies, died at the age of 63. His influence and financial backing would be sorely missed in the coming years.

The rest of the season saw United yo-yo up and down the league table. They put five goals past Villa, Derby and Leicester in the league and seven past Brentford in the cup (although they were ultimately knocked out by eventual winners Blackburn Rovers in the sixth round), but they conceded five to Everton before Derby got their revenge with a 5-0 win of their own. By the end of March, United were second from bottom, supporters were grumbling about the way the club was being run and attendances were shrinking.

On April 21st, it looked as if the return to the second division was inevitable as the Reds slumped to a 2-1 home defeat to relegation rivals Sheffield United. There were just three games to go and United needed to win all of them to stay up. Miraculously they did just that by edging out Sunderland and Arsenal with scores of 2-1 and 1-0 respectively, before hammering Liverpool 6-1 at Old Trafford on the final day to finish in a safe 18th place.

Sadly, Barson had played his last game for the club when attempting to make a comeback from injury, he suffered yet another one at Portsmouth. He was given a free transfer to Watford in the summer.

The following season saw United struggle once more. A string of injuries to key players again proved to be their undoing, leading to more criticism of the directors from the supporters who believed they should have been investing more money into the club and securing more quality signings instead of spending small amounts on endless cheap one-game-wonders. This would only intensify in the next couple of years. Following a sequence of sixteen league games without a win, the club's response was to bring in another couple of low budget players. Luckily, one of these was to prove an unlikely hit.

Tommy Reid had been signed from Liverpool, where he usually featured in the reserves. Upon being thrown into the thick of first-team action at United, however, the Scot striker managed an impressive 14 goals in 17 appearances - alongside strike partner James Hanson (who chipped in with 20 goals himself in 1928/29), he made a big contribution to United's turnaround that season. Come May, United had secured 12th place. In time-honoured style, they were knocked out of the cup in their second tie, however.

1929/30 proved to be another unspectacular struggle against threat of relegation. Eight losses in the first eleven games set the tone and in November, United received a 7-2 thrashing by Sheffield Wednesday at Hillsbrough. Once again, the cup run ended at the earliest opportunity after a 2-0 home loss to Swindon Town. The season's few high points were the 5-0 victory over Newcastle in late December and the club's first ever win at Maine Road (Reid scoring the only goal). Off the pitch, United were becoming increasingly troubled financially, as the poor football being played at Old Trafford and the growing level of unemployment combined to reduce attendances further. United needed an average gate of around 30,000 to break even, but that had not been the case for much of the decade and the debts were now racking up.

Things took a further downward turn during 1930/31. United conceded 26 goals in the first five games of the season, when they were beaten by Villa and Middlesbrough before being demolished 6-2 at Chelsea and 6-0 at home by Huddersfield Town. Newcastle then came to Old Trafford and put seven past the Reds. The disquiet amongst the support grew, the crowds shrunk and before long the Supporters Club, led by a Mr. George Greenhough, proposed a boycott if the board failed to meet with them to discuss the state of the club. Their demands were that the club find a new manager and buy some new players, invest in a new scouting system, and elect members of the supporters club to the board.

It was suggested that the match against Arsenal on 18th August should not be attended by fans and a meeting was held the day before at Hulme Town Hall with 3,000 supporters listening to Greenhough and former club captain Charlie Roberts make their cases for and against the boycott.

Greenhough insisted that as the board had so far failed to act on the Supporters Club's demands (or even to meet with them to discuss matters), the game should be boycotted. Roberts argued that the proposed action would affect the players, who were not to blame for the club's situation, rather then the board, who were. The supporters, however voted overwhelmingly in favour of Greenhough's plan.

By 3 O'Clock the following afternoon, however, it became clear that those 3,000 in attendance for the meeting were in the minority, as the match drew the highest gate of the season so far, when 23,406 turned up despite the adverse weather. Inevitably, United lost, as they did the following game, marking a sequence of 12 successive defeats.

By the end of the season, Bamlett had been let go (with four matches still to be played, Club Secretary Walter Crickmer taking over as temporary manager - presumably in an effort to save money) and United were at the foot of the table, having managed to win just seven games. They had conceded 115 goals, scored only 53 and equalled Middlesbrough's record for lowest number of points scored in a first division season with just 22.

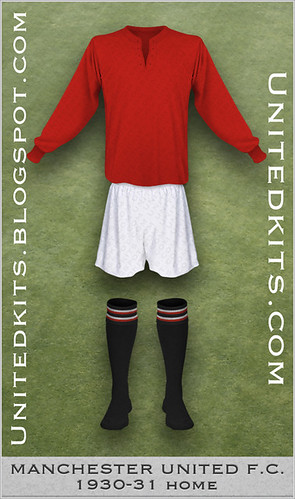

United players (Stan Gallimore centre) pictured in the 1930/31 season in new lace-necked jerseys (minus laces):

Photos on the computer screens at the United museum show players in white change shirts in the same style as the home ones:

In Justin Blundell's "Back From the Brink", United supporter Hubert Stewart, who was a child living with his family in Old Trafford at the time, reminisces about the time of the boycott:

"My father was on the committee of the Official Supporters' Club...(who) used to do their bit to help the club financially and at one time my mother took to washing the jerseys. All the women used to take it in turns to wash the jerseys to save the club's laundry bill. I can't remember how long it lasted but I can remember my mother complaining that it wasn't her turn to do them."

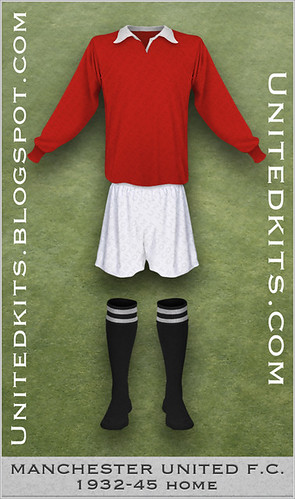

As United prepared to begin life in the second division in 1931/32 they faced financial meltdown. The economy as a whole was in dire straits and unemployment continued to rise. They club had made a loss of £2,509 the previous season and now hadn't even the cash to pay the players wages during the summer. Old Trafford was becoming a burden and the diminishing attendances were a major reason for the mounting debts. The club tried to increase numbers by reducing prices and offering tickets to the unemployed at a further reduced rate but the plans were vetoed by the FA. They had been keeping themselves above water by securing loans from Davies' widow but they could no longer rely on these to keep them afloat.

After winning just 16 points from their first 19 games, the board's belief that United would simply be able to save themselves from collapse by playing their way out of trouble on the football pitch was no more. Crowds above 10,000 had become a rarity and Crickmer had been told by the National Provincial Bank in Spring Gardens that they had withdrawn the club's credit. For the second time in 30 years, the club were close to bankruptcy.

Just like at the turn of the century, however, there was someone ready to come to the club's rescue. A local businessman and proud Mancunian, James Gibson, had been approached by local football journalist Stacey Lintott (although Louis Rocca would make a similar claim), and told of United's plight. Gibson had no interest in football, but had a reputation as someone who could turn around a failing business and as a person cared about his community. He hated the idea of such a famous institution as United becoming nothing more than a memory and so he agreed to do all he could to prevent this happening. His immediate action was to take on responsibility for the club's expenditure over the Christmas period, with the promise that if he was given enough support he would do so permanently.

After winning just 16 points from their first 19 games, the board's belief that United would simply be able to save themselves from collapse by playing their way out of trouble on the football pitch was no more. Crowds above 10,000 had become a rarity and Crickmer had been told by the National Provincial Bank in Spring Gardens that they had withdrawn the club's credit. For the second time in 30 years, the club were close to bankruptcy.

Just like at the turn of the century, however, there was someone ready to come to the club's rescue. A local businessman and proud Mancunian, James Gibson, had been approached by local football journalist Stacey Lintott (although Louis Rocca would make a similar claim), and told of United's plight. Gibson had no interest in football, but had a reputation as someone who could turn around a failing business and as a person cared about his community. He hated the idea of such a famous institution as United becoming nothing more than a memory and so he agreed to do all he could to prevent this happening. His immediate action was to take on responsibility for the club's expenditure over the Christmas period, with the promise that if he was given enough support he would do so permanently.

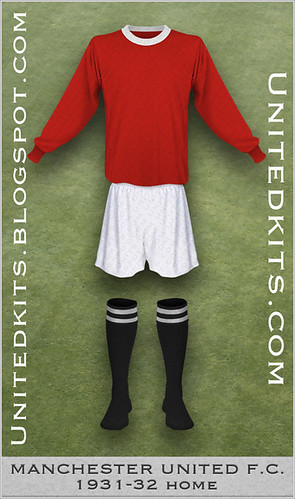

The shirts they are wearing were presumably adopted as part of the home kit at the start of the season and are remarkably similar to the style that was worn by United in the sixties. The change kits are currently unknown, but may have been the same worn during the previous season:

On January 20th 1932, Gibson took full control of the club. By this time he had done much to resolve the conflict between supporters and the management by engaging in talks with Mr Greenhough and revealing that he was already looking to bring in a new manager. He had also made public his dreams of producing a United team made up entirely of Mancunians and his wish to set up a youth team - something which would bring United great success 20 years later.

Attendances at Old Trafford started to rise immediately, several new players were brought in and the team were rejuvenated, winning ten and losing just four more matches during the remainder of the season on the way to a 12th place finish (although United - typically - were knocked out of the cup in the third round).

Attendances at Old Trafford started to rise immediately, several new players were brought in and the team were rejuvenated, winning ten and losing just four more matches during the remainder of the season on the way to a 12th place finish (although United - typically - were knocked out of the cup in the third round).

This is an edited version of an image from the extensive Leslie Millman collection, which can be found at www.flickr.com/photos/manchesterunitedman1/ and is used with full permission.

This cartoon from October 1932 dates United's adoption of the cherry and white hooped change kits to the 1932/33 season. The two games referred to are the away matches against Charlton and Burnley:

There is an anecdotal story about the hooped jerseys being given to United by Wigan RLFC as a gift to help them out when they were in financial difficulties. They are certainly of a very similar style to those worn by the Rugby League side at the time (as this photograph of Ken Gee shows), but as this cartoon suggests that the kits were first worn after the Gibson takeover (and subsequent injection of his cash), there seems to be little to back up this tale.

United's progress under Gibson continued in 1932/33 as players such as George Vose and Tommy Frame were signed and Scott Duncan was installed as manager. The highlight of the season was probably the 7-1 home win against Millwall, but the Reds' poor away form meant all they could manage was a sixth place finish. Yet again the cup campaign was over 90 minutes after it began.

For the 1933 FA Cup Final, Everton and Manchester City wore numbered shirts for what is believed to be the first time. Everton (who won 3-0) wore numbers 1-11 while City wore 12-22. The FA made shirt numbering compulsory in 1939. The exact date when United first wore numbered shirts is currently unknown, however.

The 1933/34 season was perhaps the most desperate in United's history. After they had seemed to have turned the corner since the Gibson takeover, remarkably by the season's end, the club would find itself on the brink of relegation to the third division.

The season opened with a 4-0 loss at Plymouth and it wasn't until the sixth league match away to Brentford that United registered their first win. By the beginning of December, United looked to have staged a recovery, but after the win at Port Vale on the 2nd of the month, they would only pick up three points over the next thirteen games (as well as being knocked out of the cup by Portsmouth in a third round replay during the same period). Also, for the third time in four seasons, United conceded seven goals during one of their Christmas fixtures (this time away to Grimsby Town!) .

The only league win during those thirteen fixtures was away to Burnley, where United wore the cherry and white hooped jerseys. Keen to seize upon anything that may offer United hope of escaping the drop, the "lucky" reputation of the hooped strips grew among supporters and players alike. So much so, that for the home game against Bury on March 3rd, the players turned out in the hoops at Old Trafford - and won 2-1 with goals from Jack Ball and Stan Gallimore. For the remainder of the season the hoops would remain first choice kit (presumably the solid red jerseys were used for away matches when there was a colour clash - possibly at the Dell against Southampton).

By the end of April, United found themselves teetering on the precipice. Lincoln had already been relegated and either United or Millwall would follow them. As fate would have it, those two sides were to meet in a decider at The Den on the final day of the season.

A tense, nervy affair could have been expected, but as it happened, United - by all accounts - enjoyed a comfortable 2-0 win to guarantee their place in the second division the following season. On their return to Manchester they were given a heroes welcome by around 3,000 fans at Central Station. It was a far smaller crowd than had welcomed home Manchester City's players (including a 24 year-old Matt Busby and a young goalkeeper called Frank Swift) after their FA Cup final victory over Portsmouth a week earlier*, but it marked a point where United were in the trough of the wave of success while City were at it's peak and that situation would eventually be reversed.

*A recent article in Four Four Two magazine states that the 1934 FA Cup Final was the first occasion that both sides were outfitted by Umbro, who would feature heavily in the story of United's kits.

United's progress under Gibson continued in 1932/33 as players such as George Vose and Tommy Frame were signed and Scott Duncan was installed as manager. The highlight of the season was probably the 7-1 home win against Millwall, but the Reds' poor away form meant all they could manage was a sixth place finish. Yet again the cup campaign was over 90 minutes after it began.

For the 1933 FA Cup Final, Everton and Manchester City wore numbered shirts for what is believed to be the first time. Everton (who won 3-0) wore numbers 1-11 while City wore 12-22. The FA made shirt numbering compulsory in 1939. The exact date when United first wore numbered shirts is currently unknown, however.

The 1933/34 season was perhaps the most desperate in United's history. After they had seemed to have turned the corner since the Gibson takeover, remarkably by the season's end, the club would find itself on the brink of relegation to the third division.

The season opened with a 4-0 loss at Plymouth and it wasn't until the sixth league match away to Brentford that United registered their first win. By the beginning of December, United looked to have staged a recovery, but after the win at Port Vale on the 2nd of the month, they would only pick up three points over the next thirteen games (as well as being knocked out of the cup by Portsmouth in a third round replay during the same period). Also, for the third time in four seasons, United conceded seven goals during one of their Christmas fixtures (this time away to Grimsby Town!) .

The only league win during those thirteen fixtures was away to Burnley, where United wore the cherry and white hooped jerseys. Keen to seize upon anything that may offer United hope of escaping the drop, the "lucky" reputation of the hooped strips grew among supporters and players alike. So much so, that for the home game against Bury on March 3rd, the players turned out in the hoops at Old Trafford - and won 2-1 with goals from Jack Ball and Stan Gallimore. For the remainder of the season the hoops would remain first choice kit (presumably the solid red jerseys were used for away matches when there was a colour clash - possibly at the Dell against Southampton).

By the end of April, United found themselves teetering on the precipice. Lincoln had already been relegated and either United or Millwall would follow them. As fate would have it, those two sides were to meet in a decider at The Den on the final day of the season.

A tense, nervy affair could have been expected, but as it happened, United - by all accounts - enjoyed a comfortable 2-0 win to guarantee their place in the second division the following season. On their return to Manchester they were given a heroes welcome by around 3,000 fans at Central Station. It was a far smaller crowd than had welcomed home Manchester City's players (including a 24 year-old Matt Busby and a young goalkeeper called Frank Swift) after their FA Cup final victory over Portsmouth a week earlier*, but it marked a point where United were in the trough of the wave of success while City were at it's peak and that situation would eventually be reversed.

*A recent article in Four Four Two magazine states that the 1934 FA Cup Final was the first occasion that both sides were outfitted by Umbro, who would feature heavily in the story of United's kits.